In one fell swoop, the United States has taken out the two masterminds

behind Iran’s policy in Iraq.

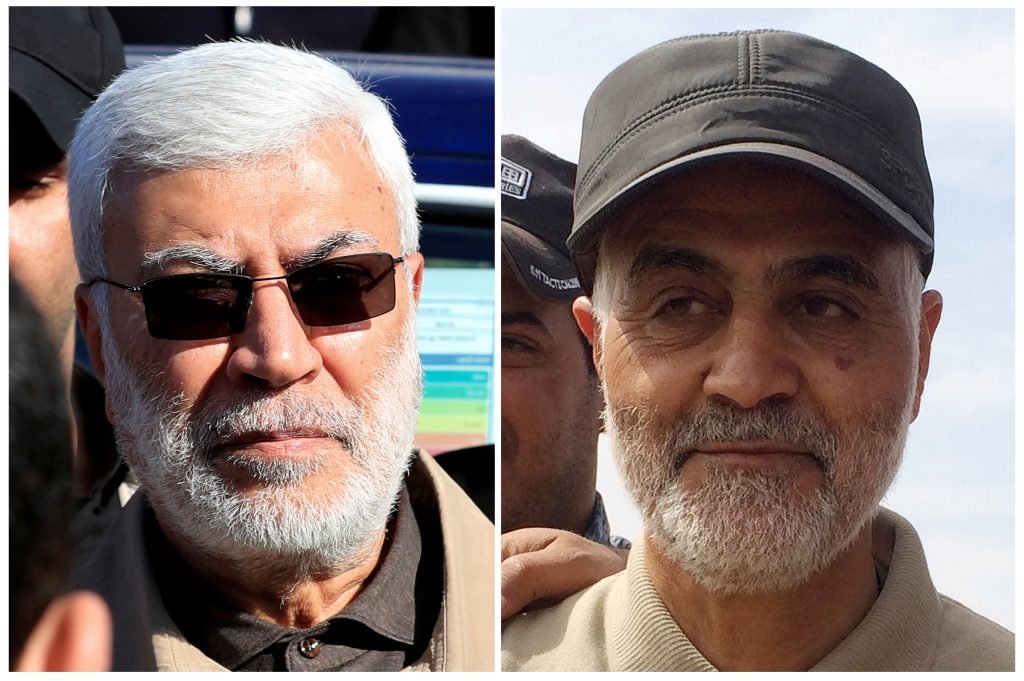

Overnight, the President ordered a drone strike that killed Major General Qassem Sulaymani, the commander of Iran Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corp’s Quds Force. Sulaymani was the most powerful man in Iraq, having masterminded Iranian policy there for over a decade.

He was also arguably Tehran’s greatest asset in the geopolitical struggle for the Middle East, masterfully manipulating events across the region to suit Iran’s interests and repeatedly outmaneuvering the United States. For his remarkable accomplishments, Sulaymani was not only highly respected among Iran’s leadership, but also admired by many average Iranians. Some even thought him a future leader of the Islamic Republic.

The same drone strike that eliminated Sulaymani also killed Abu Mehdi al-Muhandis, the de facto commander of Iraq’s Hashd ash-Shaabi (Popular Mobilization Forces, the Shi’a militias that now constitute a parallel military within Iraq). Muhandis was probably Iran’s most important and capable Iraqi proxy. He was also responsible for multiple attacks on US forces, as well as fatal assaults on anti-government and anti-Iran Iraqi protesters over the past two months. There are also reports, unconfirmed as of this writing, that US forces simultaneously captured two other key Iranian proxies, Hadi al-Ameri and Qais al-Khazali, the commanders of Iraq’s Badr and Asaib Ahl al-Haq militias respectively.

This was a tremendously daring and risky move by an administration that in the wake of previous Iranian attacks in the region (and on Americans in Iraq) had shown an overriding desire to avoid conflict. Stranger still, this strike on one of Iran’s most senior military leaders could easily provoke a violent response.

A key question at this early hour is the extent to which the attack was

pre-planned, and therefore how well positioned the United States is to exploit

this opportunity or deal with an Iranian response.

There is some evidence to suggest that a certain amount of planning and

consideration went into this dramatic shift in policy. Defense Secretary Mark

Esper warned earlier in the day that the United States had intelligence

indicating that Iran was preparing more attacks on US targets in Iraq. While

the killing of Sulaymani and Muhandis on its own might have been the result of

a sudden intelligence tip — a SIGINT hit indicating their location and

vulnerability to attack for a limited period of time — if the drone strike

occurred simultaneously with raids to capture Khazali and Ameri, that too

would indicate an operation developed over a longer period of time.

Caution must be the watchword in this analysis: The news about Khazali

and Ameri remains unconfirmed, and Esper’s warning on its own is

a much slimmer reed on which to base the idea

of a properly staffed and considered decision. After all, this is the

Trump administration, and we cannot assume that there was any process at

all. It may simply have been that the US got an unexpected

tip-off and Trump ordered the drone strike on the spur of

the moment. Certainly, US forces in the region do not appear

to have been postured or reinforced to deter Iranian

retaliation for a move like this. That suggests that these actions may have

been taken with only minimal prior planning, let alone preparation

for likely Iranian retaliation in some form.

Iran will have two basic choices ahead. It could respond angrily and immediately. Iraqi supporters of the various Iranian-backed militias could again attack the US Embassy in Baghdad, and might do so with or without explicit instructions from Tehran. Those same militias might mount rocket or mortar attacks on US bases in Iraq. The Iranians themselves might choose to fire ballistic missiles at those same bases simply to demonstrate that they will respond with force to American uses of force. They could launch cyber-attacks against American targets anywhere in the world, assuming that they had those attacks already prepped and ready to launch.

On the other hand, Iran might decide to wait and respond at a time, place, and manner of its own choosing. Tehran does not seem to want a war with the US (although the Sulaymani killing might change that) and may refrain from lashing out in a way that could invite an even more lethal American response. Or the leadership might opt to launch new attacks on the oil exports of America’s Gulf allies, as they have with impunity over the past six months. Iran’s terrorist and unconventional warfare capabilities are formidable and its leaders have often recognized that they are better able to compete with the US in these areas than in an overt, conventional war.

Accordingly, Tehran might opt for a tit-for-tat response, killing and/or kidnapping senior American diplomats or military commanders. Iran might also mount larger terrorist attacks against American targets in the Middle East, or conceivably beyond it. In all of these cases, however, the leadership of the Islamic Republic would almost certainly have to wait to identify targets of opportunity and then develop a plan to hit them. It is unlikely that they could execute such operations on the fly.

And of course, Iran and its Iraqi allies — not to speak of multiple

additional proxies throughout the region — might also choose some

combination of the two.

For the United States, all of this creates both risks and opportunities. If

Iran does lash out in retaliation, either now or later, and does significant

damage to American interests, Washington will need to respond. As bad as the

damage done to Iranian interests by the elimination of these actors has

already been, if the Iranians are allowed to retaliate and cause

largescale damage without an American response, it will reinforce their

perception that President Trump has no stomach for a protracted fight. They

will believe that they have escalation dominance, which will encourage them to

continue to use force against the US and its regional allies. While determined

American military responses that inflict real pain on the Iranian

regime are the best way to convince Iran to cease and desist from

further attacks, they also raise the risk of starting an escalatory spiral with

an angry Iranian leadership that could lead to a wider war.

It is also worth noting that this strike reduced the prospect of near-term US-Iranian negotiations over a new nuclear deal from unlikely to unimaginable. Tehran is not going to sit down and talk to the Great Satan after we just killed their greatest military commander.

Notably, the great opportunity for the United States that follows from the elimination of Sulaymani and Muhandis lies not with Iran, but with Iraq. The strike will send an unexpected message to Iraqis that Washington is willing and able to hit Iran in Iraq, and inflict real pain on Tehran and its Iraqi minions. That is the kind of message from the United States that Iraqis have not heard since the withdrawal of American troops in 2011. It is one that they will pay attention to. Moreover, the killing of these two quasi-omnipotent leaders will diminish Iranian influence in Iraq for some period of time. If the US wanted to move Iraq’s broken politics in a more constructive direction, now would be the time to do so. The Iraqis will be more willing to listen to American suggestions, and less fearful of crossing the Iranians than they have been in almost a decade. The key is whether the US is prepared to move Iraqi politics in a better direction and whether the Trump administration is even interested in doing so.

The post The Trump administration is suddenly all-in on Iran in Iraq appeared first on American Enterprise Institute – AEI.