Antibiotics are one of the greatest discoveries in human

history, yet they don’t last forever — within a few years resistance to each

new medicine makes them less effective and sometimes useless. So it is

important that the medical community follow sensible protocols to protect the

lifespan of each product.

Such protocols are largely followed in most organized western settings. Many physicians overprescribe medicines and hospitals could be better about cleanliness, but by and large physicians do not prescribe the wrong medications and hospitals do not dispense them either. So even if over-prescribed, someone with a mild infection will be given amoxicillin or other first-line treatments, and only if that doesn’t work will they be given a second-line treatment, such as a carbapenem. But in emerging markets many precious second-line medications are widely available and presumably used inappropriately.

India makes every product, often with Chinese ingredients,

and they are the cheapest products in the world. India is also incredibly poor,

where sanitation is often lacking and where antibiotics are used as substitutes

for better hygiene.

While second line antibiotics are not cheap compared with

first line treatments like cipro or amoxicillin, patients can at least buy them

when they or their dependents inevitably get sickened due to poor sanitation

and first-line treatments do not work. Clinical failure may be due to

resistance but just as often because of substandard production. But regardless,

inappropriate use of second-line treatments occurs.

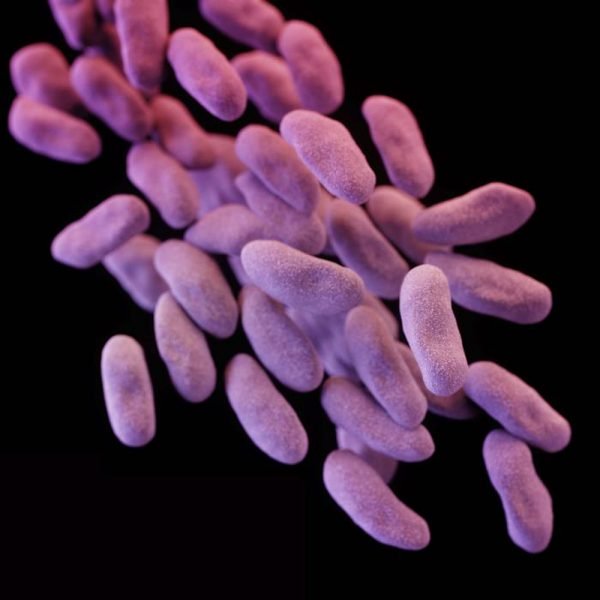

The trade is so pervasive that it’s possible to buy these products without even a prescription. In my ongoing research into Indian medicines I started to look at sales of a key second-line treatment – carbapenems. As can be seen below, in three separate samplings from three Indian cities, a sizeable percentage of regular pharmacies sold the products and in most one could buy them without a prescription.

Although the situation improved in 2018 an alarming number of establishments were still selling carbapenems, a critical second-line type of antibiotic.

Perhaps worse still is that many of the products are

substandard in some way or other. In a few instances 25 percent don’t work and

at best 8 percent fail.

What this means is that patients are taking products that may be suboptimal, could have side effects, should be supervised by a medical professional and may drive resistance. As concerns about antibiotic resistance rise, Indian lack of oversight of medicine sales is arguably one of the most irresponsible actions in public health today.

The post Drivers of antibiotic resistance appeared first on American Enterprise Institute – AEI.