Technological progress isn’t inevitable. History is replete with examples of resistance. It wasn’t just the Luddites. For example: Queen Elizabeth I famously refused to grant William Lee a patent for his stocking-frame knitting machine, a key invention in the mechanization of the textile industry. “Consider thou what the invention could do to my poor subjects,” the English monarch said, as recounted in The Technology Trap by economist Carl Benedikt Frey. “It would assuredly bring them to ruin by depriving them of employment, making them beggars.”

A more recent example is the unfortunate rejection of nuclear power by Japan and Germany. In those cases, government cast a vote against progress. Yet the story of technological advance isn’t just one of government neutrality but rather, as economic historian Joel Mokyr has written, of government “consistently and vigorously siding with the ‘party’ for innovation.” Great Britain tried to actively suppress the Luddite uprising, including the deployment of some 12,000 troops. It was a force, Frey notes, bigger “than the army Wellington took into the Peninsular war against Napoleon in 1808.”

Pro-innovation policy is

more varied today. Taxes, regulation, immigration, education, infrastructure,

and research spending are all part of the mix. And perhaps the precise

portfolio weighting is less important than the action of allocation into all

sectors. If America wants to remain the planet’s leading technological power,

one constantly pushing forward the frontier, then it’s far more important what

Washington does here than its actions are over there.

Yet Washington seems distracted at best. “The US responded to the rise of the USSR and Japan by focusing on innovation,” writes tech analyst Dan Wang in his excellent end-of-year note. “It’s early days, but so far the US is responding to the technological rise of China mostly by kneecapping its leading firms. So instead of realizing its own Sputnik moment, the US is triggering one in China.”

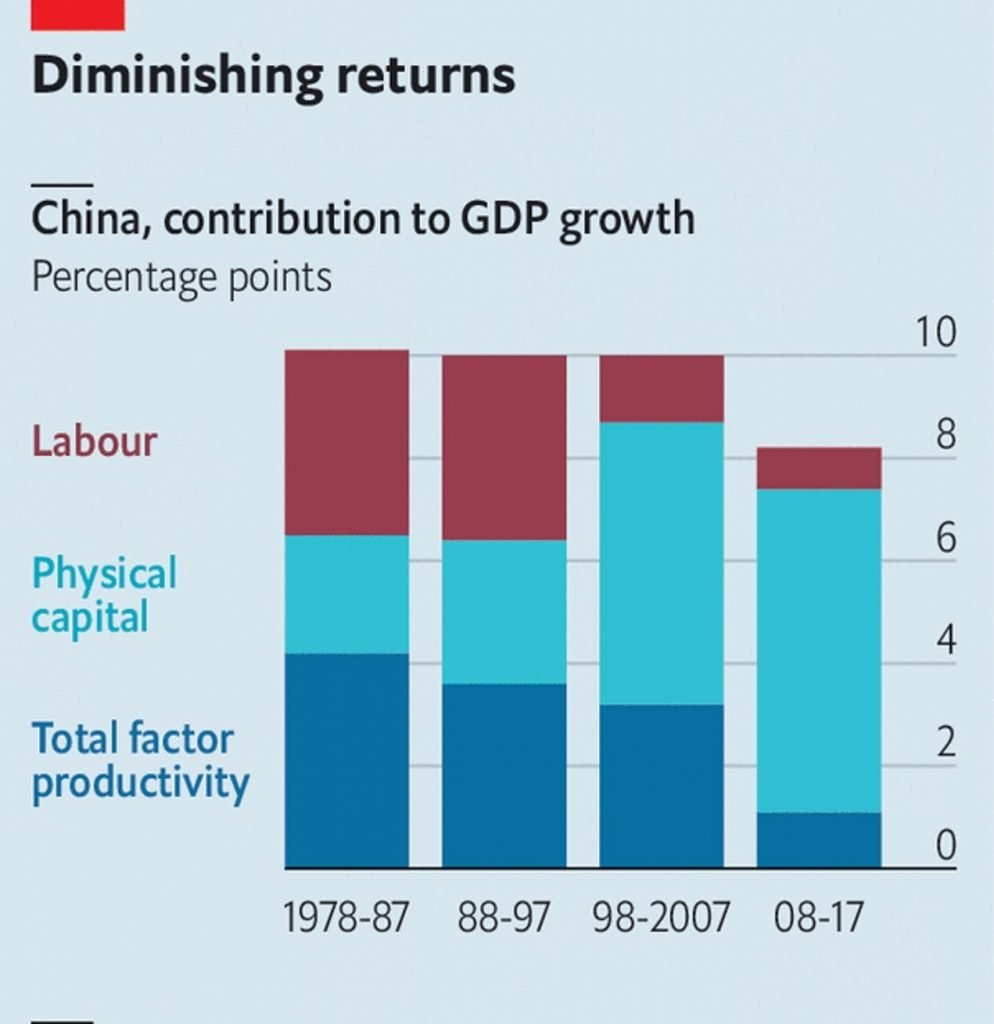

Maybe that unbalanced reaction partly stems from a lack of confidence in the American method of invention and innovation that combines entrepreneurship and public investment. China’s rapid rise and American economic stagnation seem to have persuaded some policymakers that Washington has much to learn from the planners in Beijing. But before we adopt Chinese state capitalism with American characteristics, maybe it’s worth taking in this chart from a new piece in The Economist on Chinese industrial policy:

That decline in total factor productivity — a rough measure of growth due to technological and organizational innovation — is particularly noteworthy given China’s massive program of industrial subsidy. From that Economist piece: “There is evidence that China’s heavy-handed intervention is becoming increasingly ineffective. Total factor productivity growth in China in recent years has been a third of what it was before the 2008 global financial crisis. Productivity has also slowed in other countries, but the World Bank, in a recent book about Chinese innovation, notes that China’s slowdown has been unusually sharp.”

Or as The Wall Street Journal’s Greg Ip wrote of China last year, “… the country’s state-led growth model is running out of gas. … Absent a change in direction, China may never become rich.” And what is the American growth model going forward? A pretty good question to ask in a presidential election year.

The post America should neither fear nor envy the Chinese economic model appeared first on American Enterprise Institute – AEI.